Monumental

Michael Heizer's City 1970-2022

Written By: CLARE SAUSEN

45°, 90°, 180°, City © Michael Heizer. Courtesy of Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Ben Blackwell

The Nevada desert is a haven for pushing the limits of human perception. From supposed sightings of unidentified flying objects to the ceremonial burning of a wooden effigy to cleanse a community of its regrets, it’s a place for freedom from our typical boundaries.

The climate itself is attuned to these oddities: scorching days giving way to shivering nights, sudden snowfall in typically barren areas, and rapidly accelerating zero-visibility dust storms. Even despite its connection to the infamous Area 51, there’s a distinctly Martian sense about the arid land.

In a setting free from the markers of our synthetic world, the Earth itself feels sculpted for the psyche to explore. Scale is tested, and an overwhelming feeling of smallness ensues.

A lack of belief in mirage, mind expansion, and mystical thinking need not apply.

Such is the scope of Michael Heizer: a visionary land artist defined by a passion for impact, precision, and the marriage of natural and sculpted forms. Born in Berkeley, CA, to a family of distinguished engineers and archaeologists, Heizer often struggled to meet the high academic standards set before him. What he lacked in grades, however, he made up for in spades with demonstrations of insightfully early artistic ambition.

He debuted his first works in New York at the age of twenty-two: geometrically-patterned canvases painted in latex. Non-traditional shapes and the interplay between positive and negative space soon became staples of his artistic presence.

Influenced by his father’s archaeological work and trips to ancient sites, Heizer became a pioneer of land art. This interest in space as a medium soon led him from New York to the deserts of Nevada and California, playgrounds for the burgeoning artist to mold his vision from the vast landscape at his disposal.

Here, he experimented with negative sculptures, removing chunks of the desert floor to create empty subterranean forms. Committed to utilizing naturally sourced materials, he began to experiment with white lime powder and aniline dyes to create birdʼs-eye views of amorphous, colored shapes from the sky.

By twenty-five, he showed Double Negative: a monstrously ambitious project featuring fifty-feet-deep, thirty-feet-wide parallel trenches spanning 1,500 feet across the desert.

Three years later, he broke ground on what would become his life’s work: City.

Three years later, he broke ground on what would become his life’s work: City.

Michael Heizer, City, 2023 Photo: © Annie Leibovitz

Five phases, forty million dollars, and fifty years later, City is the largest contemporary artwork ever built. Spanning over a mile long and a quarter mile wide, the scale is akin to the National Mall.

City is explored on foot: no maps, no routes, and no single viewpoints. The discovery process is gradual, beginning with subtle terrain shifts that soon give way to constructed forms (and, of course, their shadows), making the environment totally immersive. In other words, there’s no way out but through.

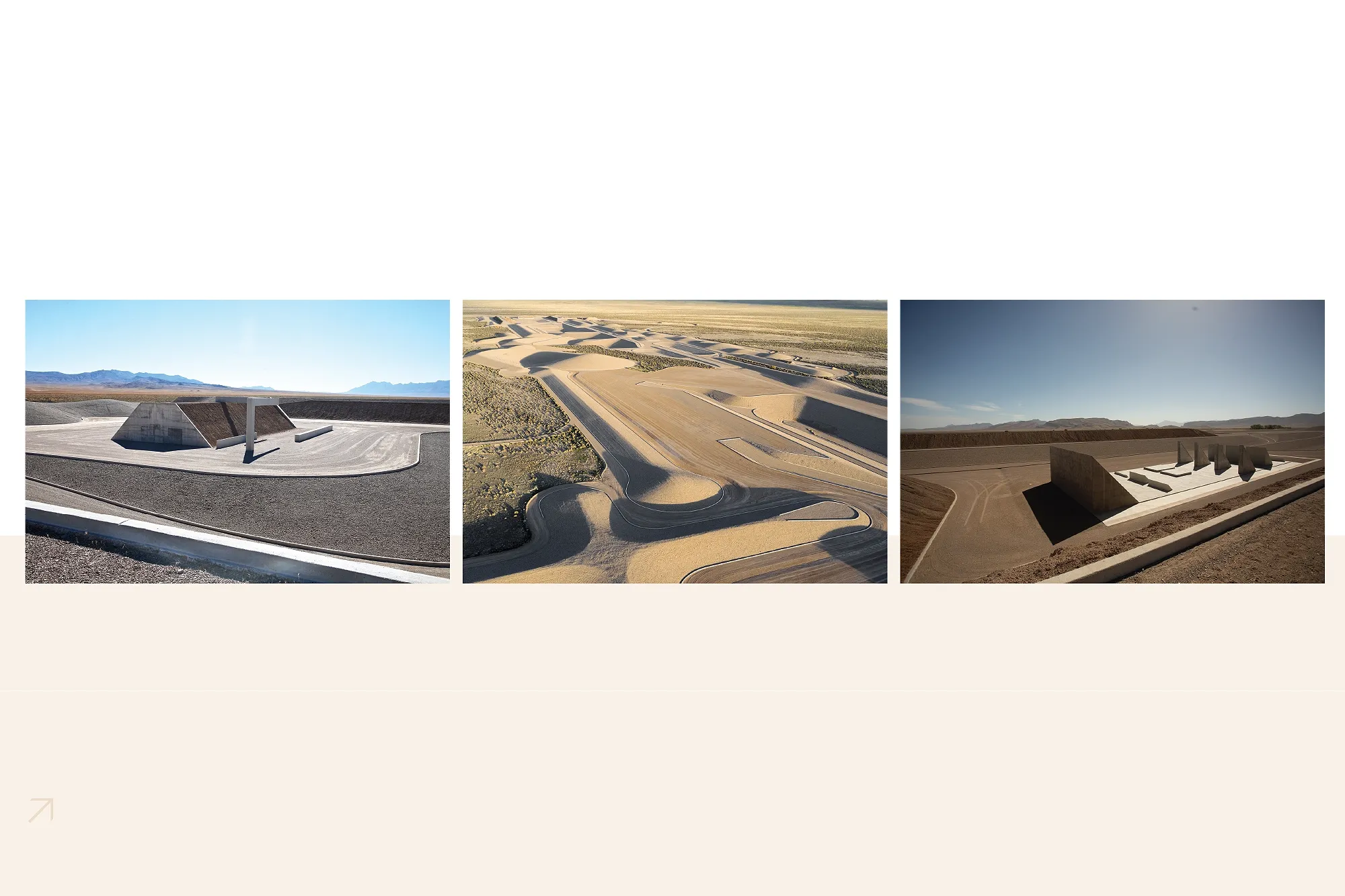

Despite the name, the piece is not our typical vision of a modern metropolis. Instead, it features earthworks, sculpted terrain, roads, mounds, depressions, and monumental structures to evoke prehistoric forms. Geometric slabs of sand and cement invoke the ancient ruins of Mayan and Incan architecture. The title plays with Heizer’s interest in opposition, centralizing his installation as a nuclear hub; monumental in scale, mythical in the art world, and magical in the desert.

Garden Valley, a rural patch of land in Nevada’s Lincoln County, stretches out like the inside of a dream (or nightmare, depending on your perception): vast, lonely, and, yes, alien. Located fifty miles north of the back gate to Area 51 is a desert that seems to hum at its own frequency, horizons pale and heat deluding. Where City rises, shadows shift like a living organism. Structures seemingly not built, but unearthed: waiting under the sand.

Enormous geometric forms: otherworldly signage or monuments to a forgotten god?

It speaks to an architectural language of awe: an echo from the pyramids of Giza or the Incan terraces of Peru, now residing on ancestral lands of the Nuwu (Southern Paiute) and Newe (Western Shoshone).

Walking City is like stepping through a living mandala, each curve and incline designed to pull the eye out and the mind in. It’s impossible to absorb all at once; shifting while in motion and shy to most photography. There’s no clear start or end to the installation. Upon entrance, your field of vision is swallowed by sculpted earth and concrete triangles. Each step pulls you deeper into Heizer’s world—and, hopefully, your own.

One visitor described the soundscape as “quiet as anywhere I’ve been apart from an anechoic chamber,” emphasizing the oft-mentioned crunchy gravel underfoot. “When you get going, you’re hyper-aware of the crunch every time you take a step.”

It’s hard to decipher if City is aesthetically closer to the ruins of an ancient civilization or the launchpad to a future one.

Enormous geometric forms: otherworldly signage or monuments to a forgotten god? In the dichotomy lies the answer: a humbling experience both foreign and deeply familiar. Visitors report feeling dwarfed, disoriented, and even altered in a world where art forces the mind to expand to its scale.

From left to right: Complex One, City. © Michael Heizer. Courtesy Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Mary Converse, City, 1970 – 2022 © Michael Heizer. Courtesy Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Eric Piasecki, 45°, 90°, 180°, City. © Michael Heizer. Courtesy Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Joe Rome

Another visitor calls the work “a mausoleum,” going on to describe “a city distilled to gravel and curbs, completely empty of the chaos of people.”

The pilgrimage is an essential part of the experience, wherein only six visitors are allowed per day (on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, May 6 through November 20) at $150 per ticket ($100 for out-of-state students; free for residents of Lincoln, Nye, and White Pine counties; in-state students and educators; active military and veterans; and Indigenous peoples). At the time of writing, tickets for the year are sold out.

The exact location of City remains largely secret. Visitors are reportedly picked up in the nearby town of Alamo, then driven to the site. Each trip lasts three hours, allowing each guest to tour the 1.5-mile-long sculpture on foot. There are no benches, no shade, and no exit through a gift shop; only the slow unfolding of something vast.

Michael Heizer has been building City for more than half a century: moving dirt, pouring concrete, and defying logic in Nevada’s Great Basin. Armed primarily with intuition, stubbornness, and a deep respect for the desert, Heizer shaped the land both by hand and machine.

Over fifty years, life happened: equipment failures, extreme weather, and health issues slowed progress while abandonment often loomed. Its forty-million-dollar total budget trickled in slowly—mainly via the Dia Art Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, and numerous private supporters over the decades. Side projects came and went; partners stepped in and out; the desert stayed.

Heizer began building City in 1972, constructing it piece by piece as funding allowed. The first section, Complex One (1972–1976), features a raised, slanted form inspired by Egypt’s stepped pyramid of Djoser. In the 1980s, he added Complex Two, continuing his dialogue with ancient architectural forms. This theme is echoed in later elements, such as 45°, 90°, 180°, blending geometry, monumentality, and timelessness.

© Michael Heizer. Courtesy Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Ben Blackwell

Heizer’s motivations remain ever-present today: entwined in apocalyptic dread, a conviction that modern civilization is teetering, and a desire to create something that might outlast it. “When they come out here to fuck my City sculpture up, they’ll realize it takes more energy to wreck it than it’s worth,” he told The New Yorker in 2016.

Like most fears, it’s also based in deep reverence: for the land, for the vastness, for the humbling beauty of nothingness.

City is both a sculpture and a scale experiment: a reminder of human persistence despite our relative size. Time stretches amid its slopes and trenches. It’s a constant dance between the cosmic and the immediate, the eternal and the impermanent. Though likely too exclusive for most to visit in person, there’s a spell the City casts in the imagination. There, scale and time are fluid, and the desert stretches forever.

A vast basin of silence, air shimmering, the horizon trembling like heat on a pan. Ahead: mounds of earth, carved into colossal shapes and terraces beneath the sun. You walk forward and feel it unfold: a structure that’s both map and maze, ancient ruin and future relic.

Somewhere near Las Vegas, Michael Heizer has bent the desert itself into a monument to human imagination: a place built to outlast us all, long after we can remember. Someday, the winds will reclaim it, and City will fade into a new ruin. Even then, it will whisper to anyone who imagines it—monumental, eternal, and just a little bit alien.