Punk: too tough to kill.

Written By: ERIC HISS-LLOREDA

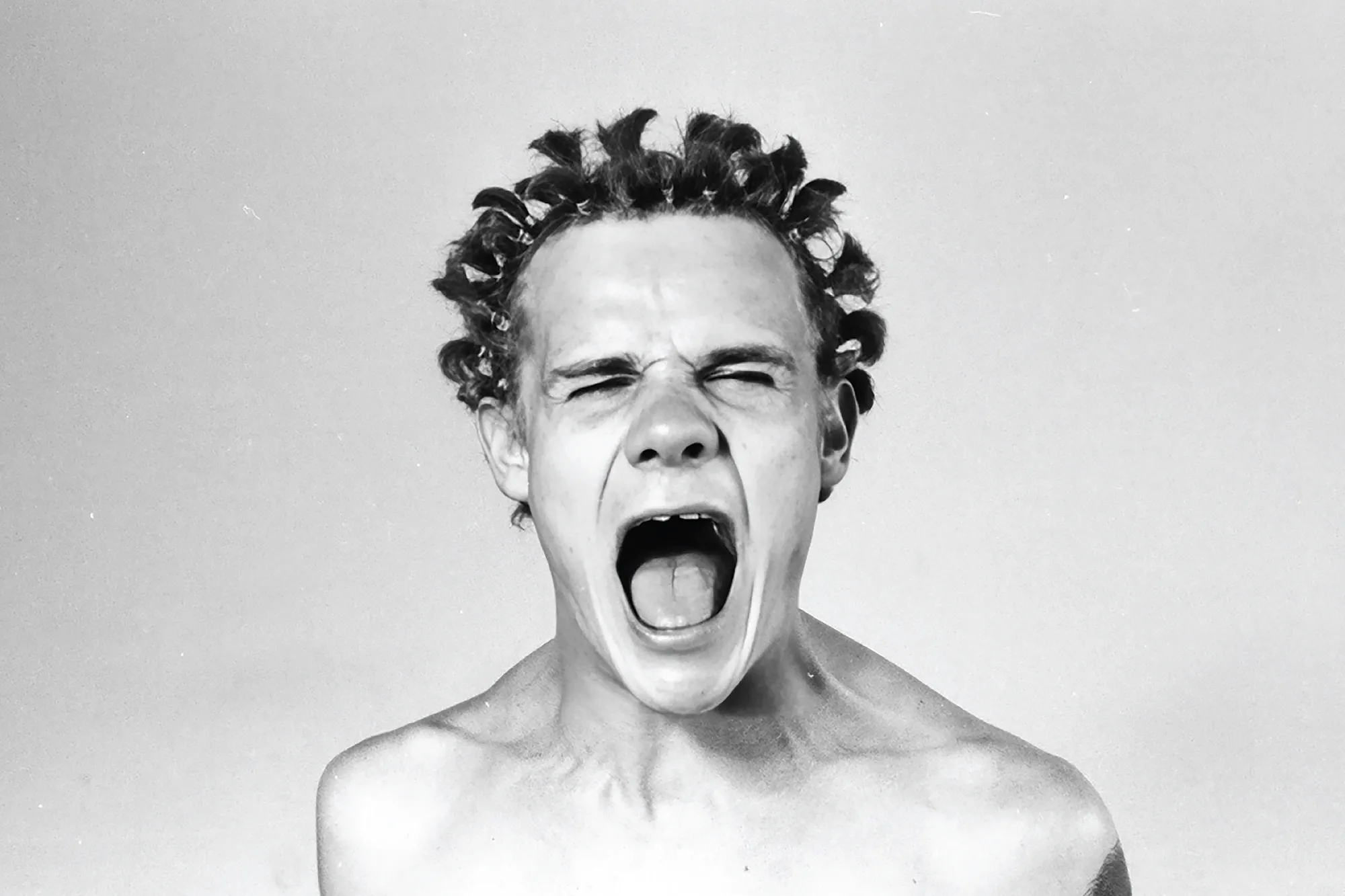

Kim Komet of Silver Chalice, circa 1980

In the late seventies, punk rock blasted like a sonic tsunami through LA. Nobody captured that world better than photographer Edward Colver.

Lounging on a veranda overlooking the verdant growth of his jungle-like backyard, at first glance, Edward Colver might not seem a likely candidate to be arguably the most important photographer to capture LA’s volatile punk scene. Tall and lanky with a thoughtful presence, he gives off a vibe that’s more antique dealer than gonzo photographer. True, his home brims with rare records, period photos, and authentic Craftsman-era furniture. But he indeed was on the frontlines during LA’s punk heyday more than 40 years ago—and he’s got the pictures to prove it.

We settle in as an early summer breeze rattles the foliage of the yard’s dense canopy of trees. To make this a proper sesh, I pop open a jar of Emerald Spirit Botanical’s Four Directions, a personal fave that’s Emerald Triangle-origin sungrown weed. I load some bowls, and we step into a time machine straight back into punk’s OG days.

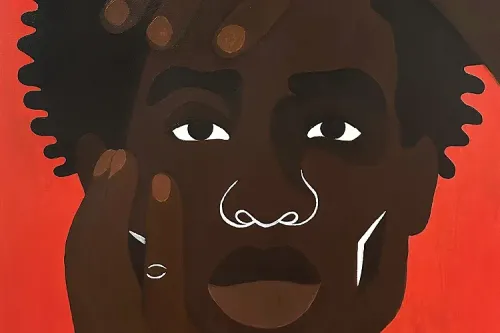

Tony Pony of Apothic Culture and Crown of Thorns, circa 1981

From the time he was growing up in the San Gabriel Valley in the sixties, Colver was always laser-focused on art. Although he wasn’t formally trained in photography, from his youth, he studied multiple forms of applied art, including printmaking, graphic design, ceramics, painting, drawing, sculpture, and woodworking. The first music that got his attention was the psychedelic sounds of the era. “I went to a lot of great shows back then,” he shares. “I saw bands like The Kinks and T. Rex, The Mothers and Captain Beefheart.” His early musical explorations also got him into avant-garde and early electronic music, but he emphasizes, “I would pay not to hear any ‘classic rock.’”

“I think a lot of my artwork addresses the demise of the American Dream…”

- Colver

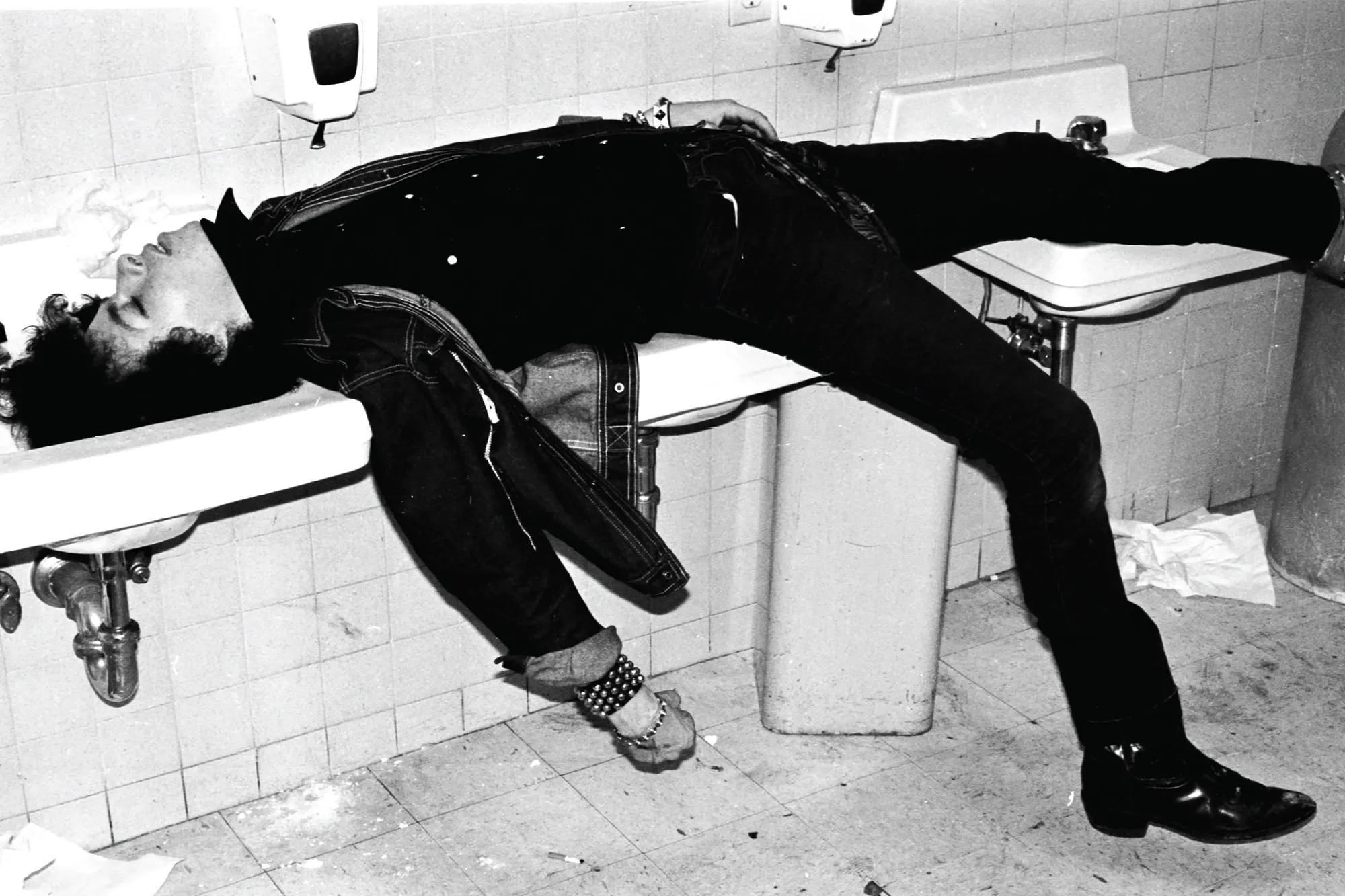

INTO THE WORLDS OF PUNK AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Exhaling after a long drag, Colver says he was bored by much of the music he was hearing in the seventies. He can’t remember the first punk show he went to, but in 1978, he acquired “a piece-of-shit” camera and started taking it to the most grim and grimy part of downtown LA to shoot some of his earliest photographs. “I started shooting at punk clubs and on Skid Row. I would drive around downtown by myself and shoot on the way home from shows. It was dangerous, but it was cool.”

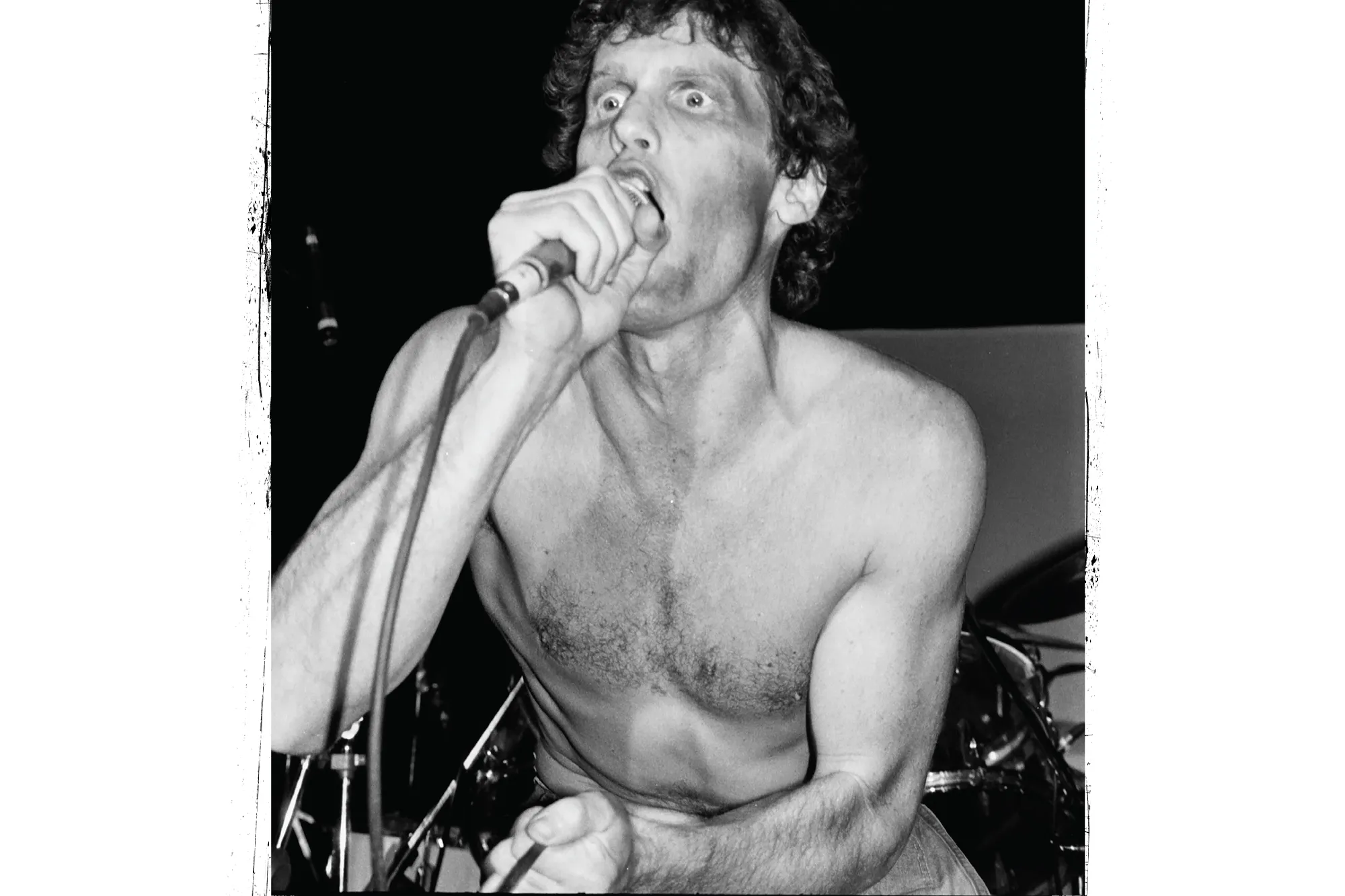

Flea of Red Hot Chili Peppers was part of the Punk Rock band Fear in the 1980s

Thinking back to those days, Colver says he was blown away by those early shows. “I was like, wow, this is incredible—there’s something really going on here—and nobody’s here to see it.” The crowds were small, fifty people was a big show, but the storm was just building. And Colver was there night after night to capture the vibe. “I was omnipresent. I went out four or five nights a week for five years—I was part of the scene and the bands became my friends. I’m still in touch with many of them.”

Musing on what drew him to the desolation and decay of Skid Row and the nihilism of the nascent punk scene, Colver says, “I think a lot of my artwork addresses the demise of the American dream. A lot of it. I’ve been doing that in one form or another for 46 years.”

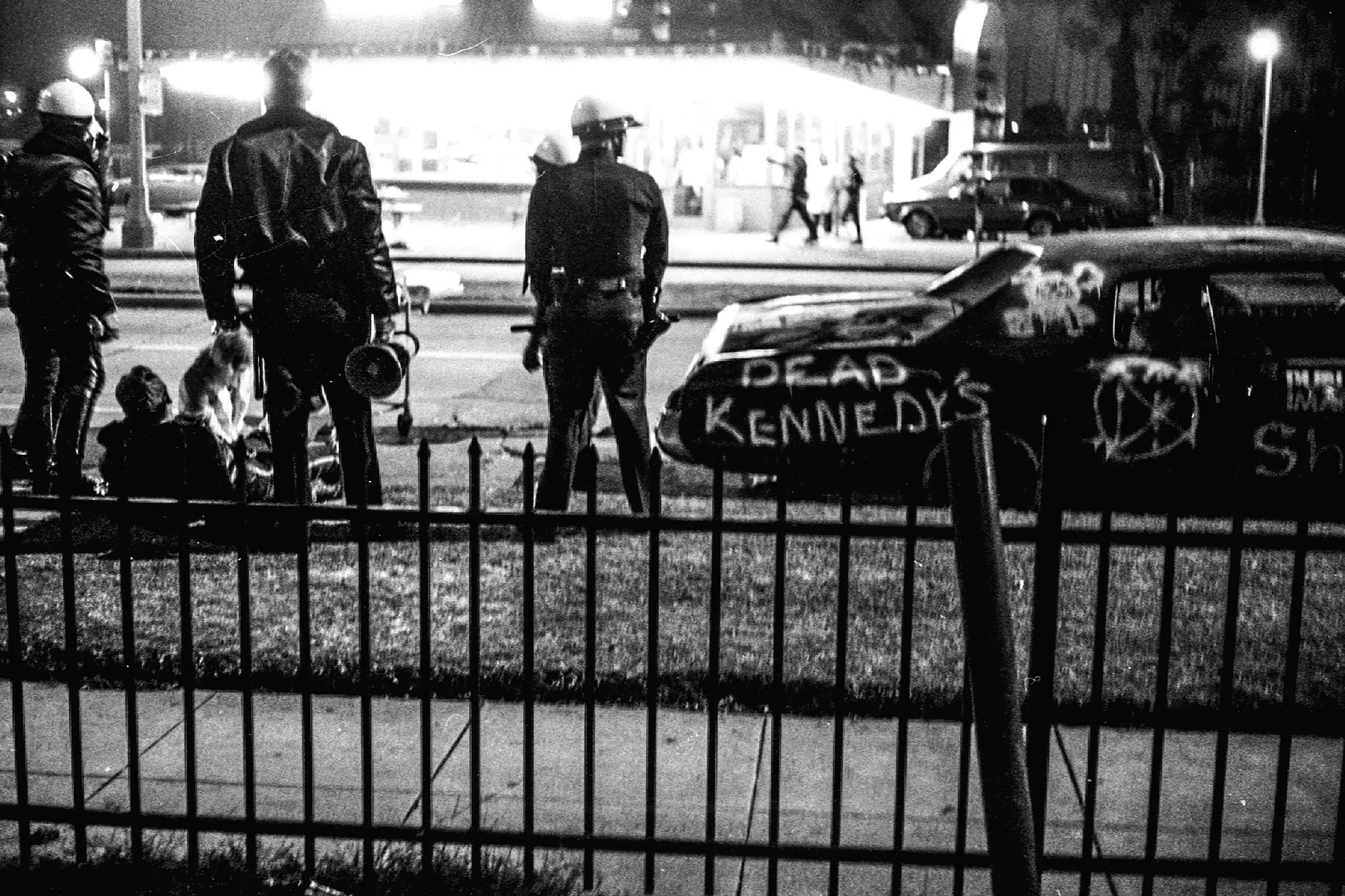

In what proves to be a timely segue to our conversation, Colver’s assistant Taylor Wong rolls up. He’s come from downtown where he was shooting photos of the confrontations between demonstrators and the LAPD and ICE during immigration sweep protests. “It’s getting bad down there,” says Wong. “They came out of nowhere, swinging at us. Unprovoked, they started shooting rubber bullets.” We look at the images on his iPhone—they’re intense: cops facing off with demonstrators, like something out of the sixties. “That’s what happened at the punk shows,” observes Colver, recalling the famous face-offs between the LAPD and punks. “Ninety percent of the time, they didn’t need to be at the shows. It was the cops showing up that caused the riots.”

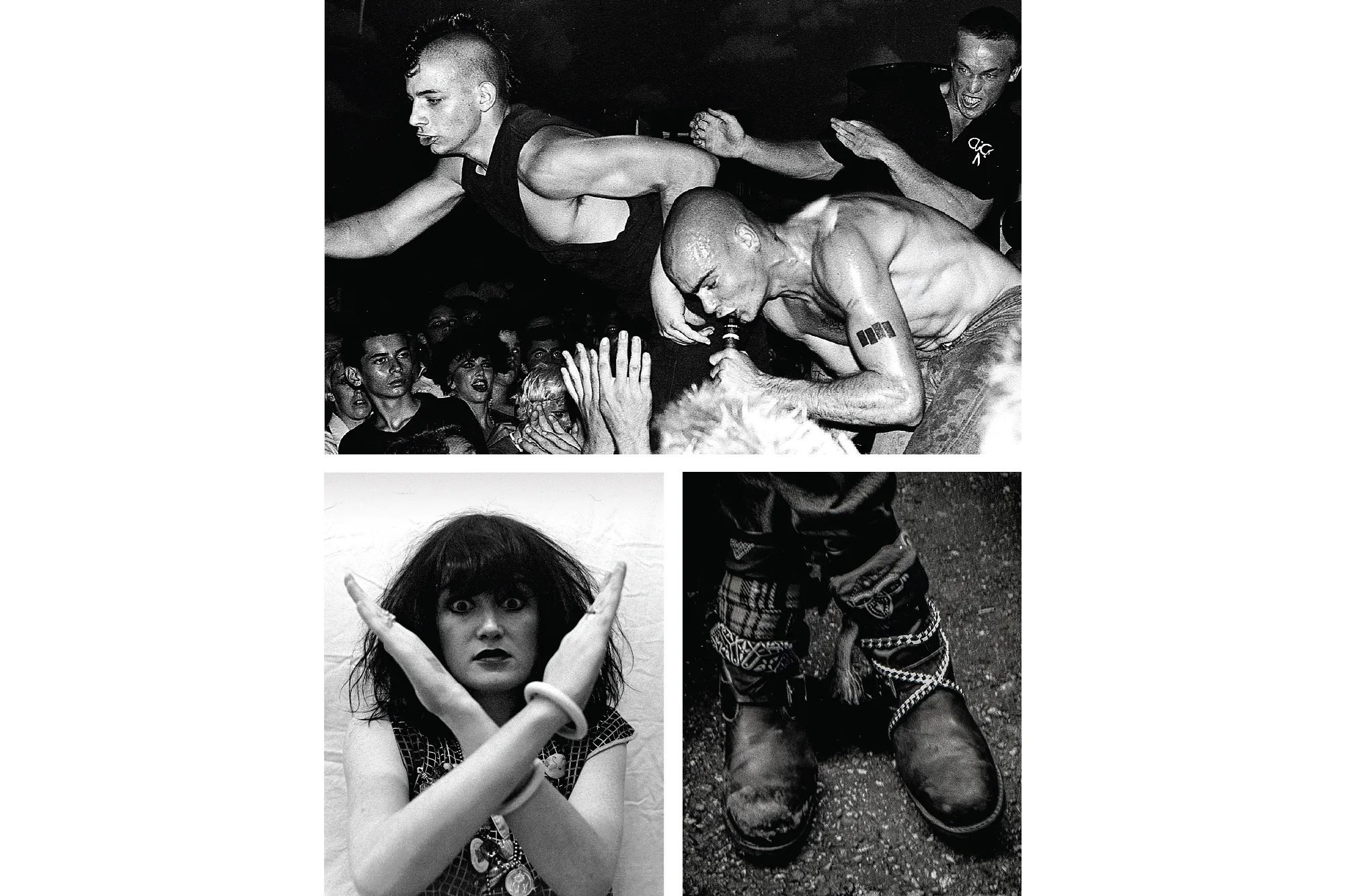

Black Flag, Punk Boots, Exene of X

A PUNK AESTHETIC EMERGES

The sesh helped us decompress from the turmoil transpiring just a few miles away in downtown and our conversation shifted to the pivotal role Colver played during the punk era. More than just chronicling the scene with his photos for popular outlets like the LA Weekly and seminal punk zine No Mag, Colver shaped the look of the bands and the emerging punk aesthetic—a world devoid of color dominated by high-contrast black-and-whites, explosive energy and unrepentant defiance. “I influenced the look of the scene—a lot. I mean, I provided photos for 80 punk records by 1983. Black Flag, Circle Jerks, T.S.O.L., Wasted Youth, Social Distortion, China White, Christian Death, Bad Religion… I did all of their first albums and many more.”

In those DIY days before digital, not only was Colver shooting cover art and additional photography but depending on the project, he also created the overall concept, designed graphic layouts and produced camera-ready artwork. “Basically, I did the entire package.”

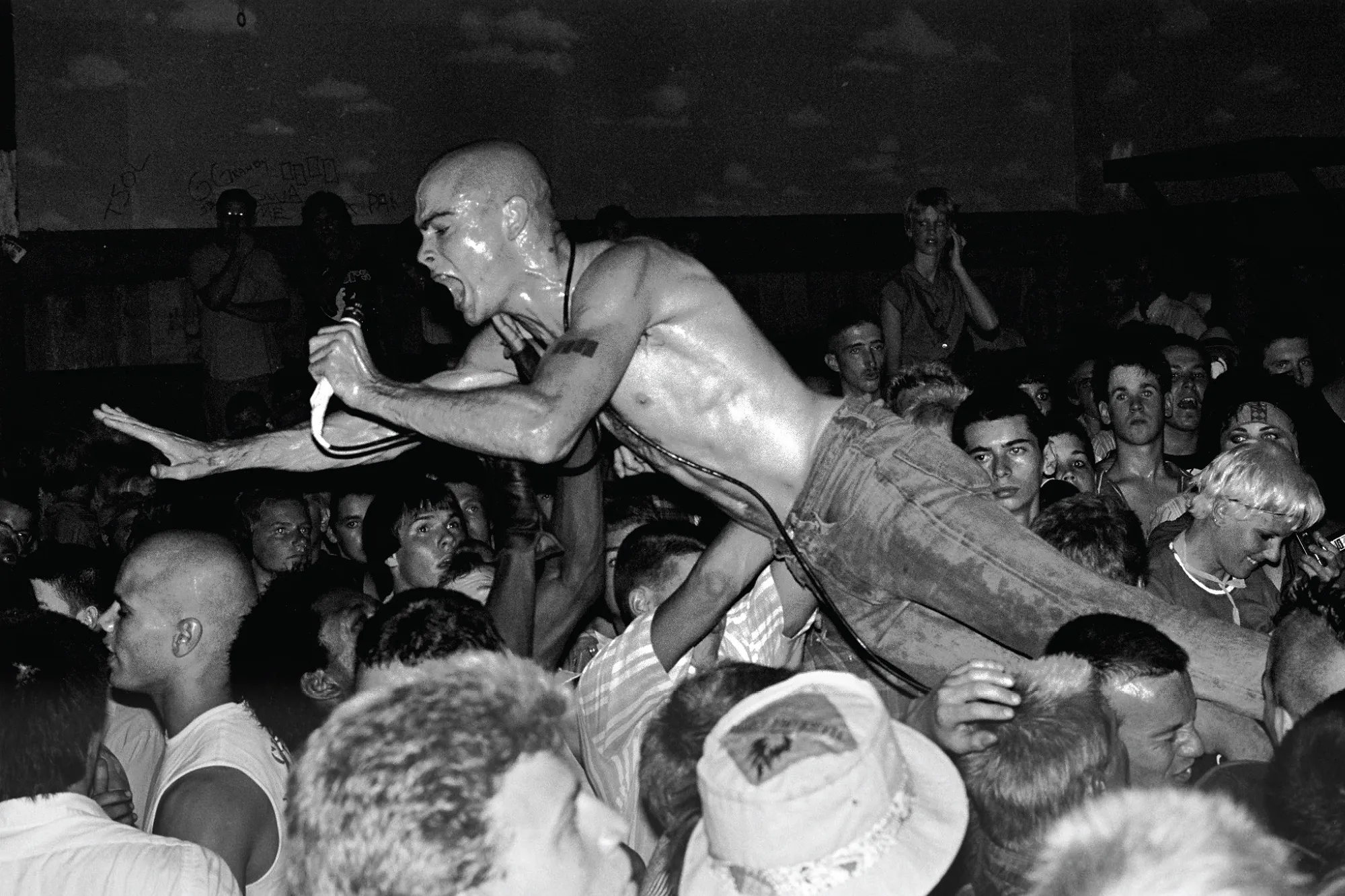

But the clubs were where Colver really stood out, both literally and figuratively. For starters, his six-foot-four frame allowed him to shoot over the crowd. And his willingness to be in the middle of the mayhem is why his shots of stage dives, snarling singers, and slam-dancing club-goers rise to the level of irrefutably epic—images that are definitive timestamps of an era that has been relentlessly copied, but never equaled.

When asked what the vibe was like in those clubs, with elbows flying and drunken dervishes swirling in the slam pit, he answers drolly, “It was fun. It was something new. It felt a little bit like being in a war zone.” As we grind up another bud, Colver riffs on what made the LA scene stand out from others.

“What was going on in LA, that was hardcore punk. I was there at the birth of it. And to me, that’s punk. People refer to Blondie and Talking Heads as punk—what the fuck are you talking about?” And don’t get him started on the gear. But I did anyway. “The British punk look was all these spikes and buttons and fucking leather jackets and Mohawks and colored hair. In LA, it was just guys in Levi’s and T-shirts, boots and flannel shirts, no bullshit.” Importantly for his work, Colver adds that this was before backstage passes and VIP lanyards arrived on the scene. “I could go wherever the fuck I wanted to get my shots.”

Texacala Jones of Tex and the Horseheads, 1982

Reflecting on the bands, Colver says the scene was a cross-section of everything from geniuses to drunken idiots—and everything in between. As he rambles off the names of bands and venues like long-lost friends, Colver gets as close to nostalgic as I’ve seen him. “The Hong Kong Café in Chinatown, that was one of my absolute favorites. Great shows there. I photographed Johanna Went there and did the photos for her single and album. The Starwood was another great club, I saw the Germs there, their last show before Darby Crash OD’d. I was also there the night a bouncer got knifed—that closed the club for good.”

“It was fun. It was something new. It felt a little bit like being in a war zone.”

- Colver

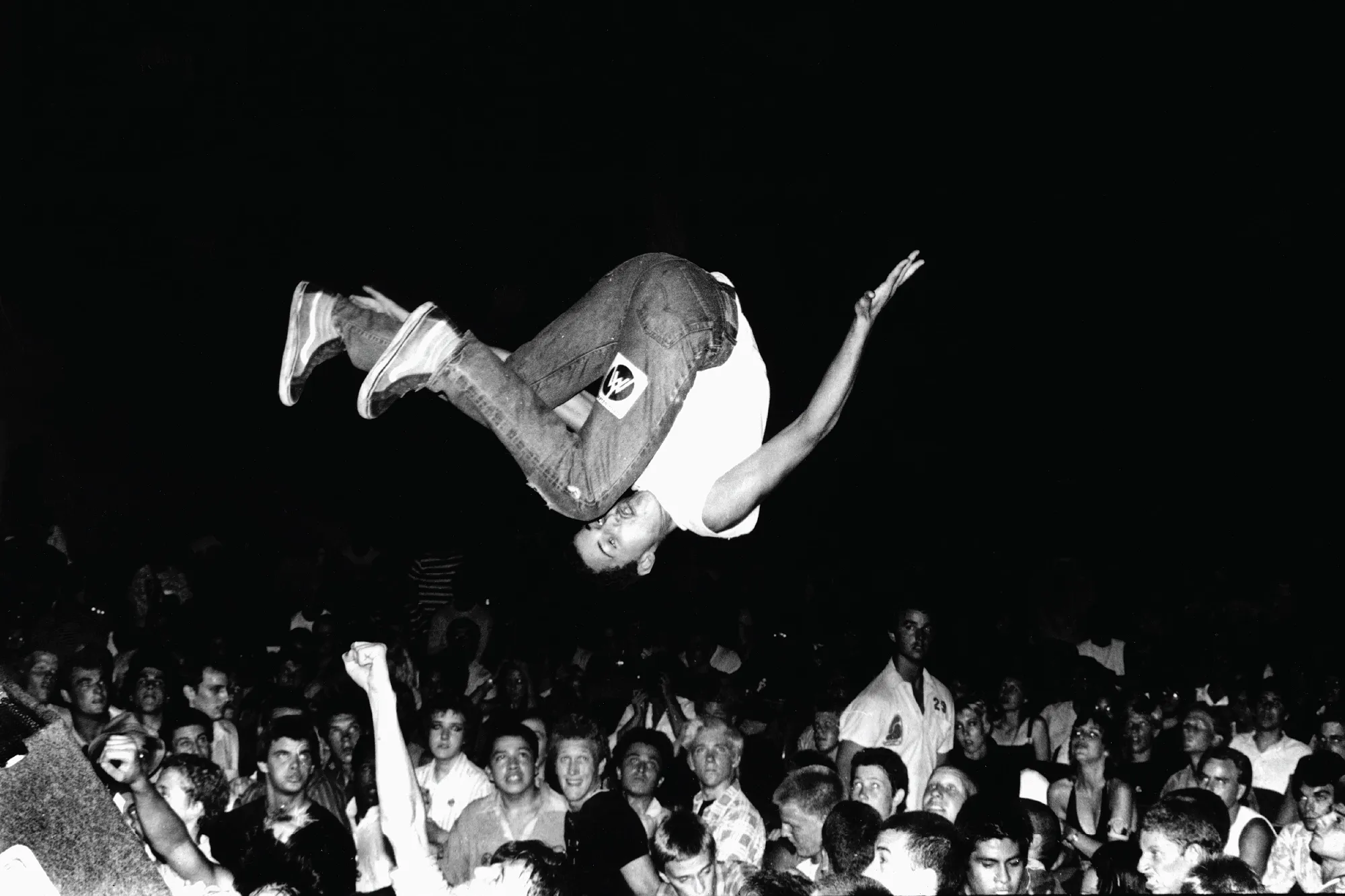

Because the SoCal punk scene was much bigger than LA proper, some of the most notable venues were in Orange County. Etched in Colver’s mind is OC’s the Cuckoo’s Nest, especially the night when Henry Rollins fronted Black Flag for the first time in 1981. “From beginning to end, all the bands were on fire, MDC, the LA Stains, it was amazing. The crowd, the music—it was a wild night. I got a photo of Henry flying through the air like Superman, about to land on the Circle One band’s John Macias.” Besides Black Flag, some of the other bands that Colver photographed at the Cuckoo’s Nest read like a hardcore honor roll, including Social Distortion, Circle Jerks, T.S.O.L., the Vandals, Christian Death, and the Adolescents.

Skateboarder Chuck Burke stage diving during a DOA, Adolescents & Stiff Little Fingers show at Perkins Palace, Pasadena, 1981

IN THE ZONE

Colver’s riff on combat photography rings true when considering the conditions he shot in—frenzied clubs with rowdy, often chemically enhanced crowds and notoriously shitty lighting. Back in the day, you needed a great eye and ninja’s intuition to nail focus, shutter speeds, depth of field, and other settings as a show roiled on. Colver eye-rolls as he disses the “spray-and-pray” methodology of some newer photographers covering live acts. “I saw someone on ‘so-so media’ (Colver’s term for social media) recently where a guy was talking about shooting 2,600 images at a show. Fuck, why not just shoot video and pull stills?” By contrast, Colver says, “I could look up and know in an instant, this shot is going to be F-8 at one twenty-fifth of a second.” It’s even more impressive when you realize he shot everything with a 50mm lens, meaning he was always right in the middle of the action.

To be ready for anything, he watched the shows through his viewfinder, poised to take a photograph at precisely the right moment. “It was like watching the scene through a keyhole, my peripheral was gone, but I’d be aware of everything happening around me.” Over thousands of shows, Colver became adept at quickly toggling between settings, using available light or a small flash mounted on his camera as the chaos unfolded. Another secret to his success was knowing the music. “I would time my photographs to the rhythm of the music. I hung out with these bands multiple days a week, and I knew when the drama was coming.”

Dead Kennedys car with riot police

PUNK EXPLODES

By the early eighties, like a shooting star, punk ignited out of nowhere to a level no one, including insiders like Colver, had anticipated. “When I first started going to shows, there were about 200 people in the punk scene in LA—half of them were in the bands, and the other half were their friends and fans. Then it caught on fire.” I ask Colver if there was a moment when he realized the scene had changed, and maybe the fire was out of control. He taps out his glass pipe into an ashtray and without hesitation answers, “The Black Flag show at the Olympic Auditorium in ’83. I looked around and there were 3,000 people and I thought, ‘What the fuck?’’’

Colver remembers the crowd getting so rowdy in the pit that night that they collapsed the barricade, shoving him into the stage. Battle-tested from innumerable shows, he managed to scramble onstage, keep shooting, and get some legendary shots of Rollins and the band from just a few feet away.

It wasn’t long after the Black Flag show that Colver decided to walk away from that world. Instead of the adrenaline and anarchy of punk, he turned his talents—and lens—to photographing recording studios as well as musicians and personalities. The bands and performers he worked with ran the gamut from R.E.M. to Flea and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, to Ice Cube and Snoop Dogg. A short list of the artists and personalities he photographed during this phase of his career also includes Andy Warhol, Tom Waits, Dr. Timothy Leary, and Chaka Khan. A cannabis smoker who avoided the pills, powders, and booze prevalent in the punk scene, Colver even styled and shot a photograph of a massive bud lit to look like a Christmas tree, featured on the cover of the 1997 High Times holiday issue. “I was paid $400 and bought an ounce with it,” remembers Colver.

Henry Rollins, a Black Flag Superman

All told, Colver contributed in some creative capacity to more than 500 albums during his career. That number wasn’t served up by Colver, but by another drop-in to our sesh: Joe Gutierrez, a longtime friend of Colver’s and former band member of punk bands The Plague and Disruptive Influence. “This guy should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Guinness World Records. I mean when he took your photo, that meant you had made it.”

A now out-of-print career retrospective of Colver’s work, Blight At The End Of The Funnel, was released in 2015. I ask if he has anything new planned. Colver says he’s currently at work with publisher The House of Blank on a multi-volume box set of his images that will cover his early Noir Skid Row images and punk photography from the late seventies to 1984. Beyond his personal legacy, I’m curious to know what he thinks about the state of punk and its more recent offshoots. “I think that punk has become a formula, and there’s about 10,000 bands that all sound the same with super-fast drumming and screaming singers, and they’re all trying to outdo each other. They all sound the same to me. In the original scene you had everything going on, all kinds of weird bands, art bands, whatever bands.”

I ask if that means punk is dead. “Sometimes it smells like it, but no. It’s the thing that won’t die. Punk is too tough to kill.” I close my notebook and lift my lighter to that one. “I think we’re good,” I say.