The Roads You Take, The Ones You Leave Behind

From Stories I've Been Meaning to Tell You by Andy Romanoff

Writing and Photography by: ANDY ROMANOFF

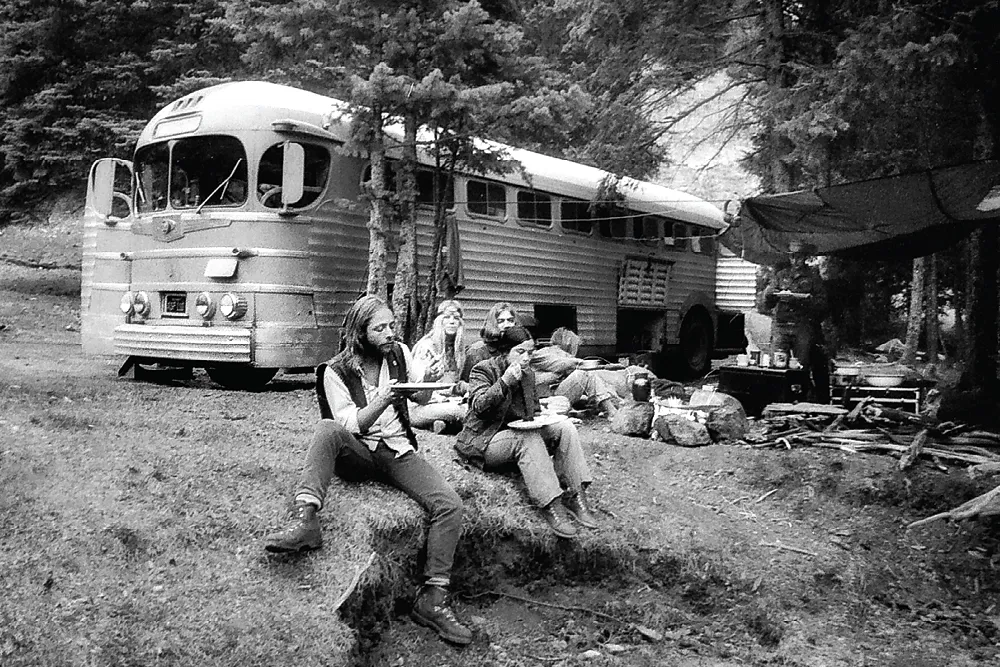

Hog Farmers eating lunch by the road, early 70s.

I joined the Hog Farm in 1970, a long time ago. I left after about a year but sometimes I’d get back on the bus for a little while—spending time hanging with my old friends, or meeting up with them at stops along the way—but as a member I was gone. I left, but I never quit. I became an executive, an Academy member, a temple goer; I lived a hundred other layers of life, gathering identities as I went. Still, always, I remembered I was a Hog Farmer.

I haven’t told you much about the beginnings of Hog Farm yet, so here’s a little more history. Before the Hog Farm there were the Merry Pranksters, a collection of acid-fueled voyagers who coalesced around Ken Kesey and built Further, the first dayglow painted party-as-life bus. After the Acid Tests, when Kesey slipped into Mexico to avoid jail time, the Pranksters split up and some of them became the nucleus of the Hog Farm. Many of those first farmers are still living together, making the Hog Farm the oldest living commune in America; a bunch of 60s hippies welded together by common desires and trust and time.

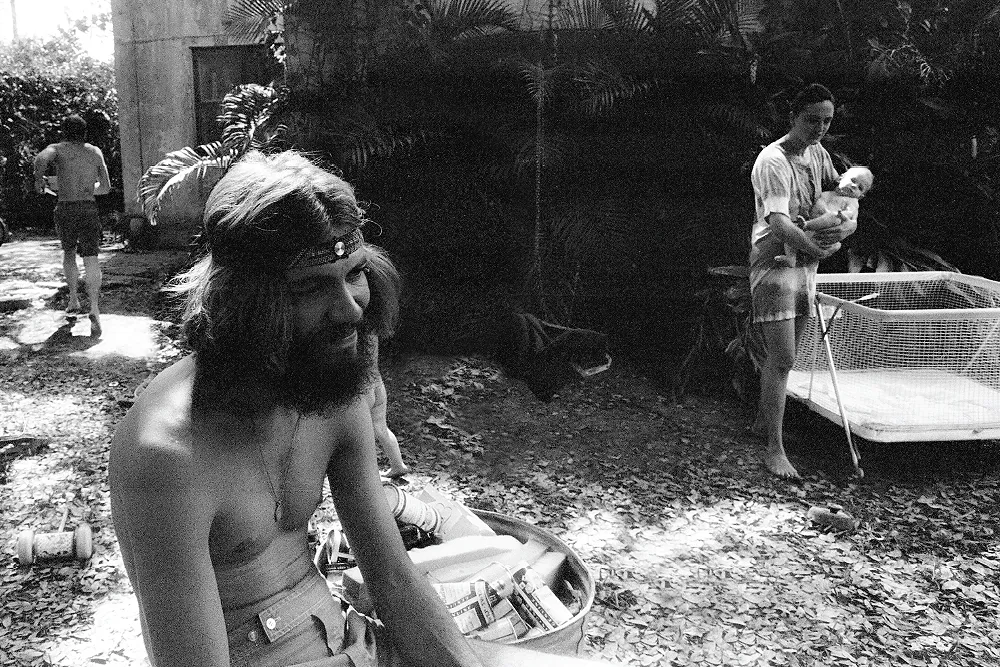

Butch, Fred the Fed, Bus boy, and a young woman whose name is lost to time, in Coconut Grove, FL, after the Winterʼs End Festival, March 1970.

They first came together in December ‘66, a handful of people living in the hills of Sunland, California, and there they built a bus to replace Further, their lost bus of Keseyfreak dreams. They called this new bus Road Hog, and slowly it was joined by many other freak-filled busses, until together they coalesced into a traveling commune. By the time I joined up the Hog Farm was back from Woodstock, and Wavy, tired of the endless cop shows as the painted busses made their way across the land was looking for new ways to do things. The bus I signed on to was called The Fast Bus or the Incredible Asp. She was a 1947 Silversides, a diesel-engined long haul machine, the first post-war bus built by the Greyhound bus line. By 1969 she probably had a few million miles on her and had been replaced in the Greyhound fleet by a newer generation of advanced and powerful machines. But to us she was truly a magic bus, a huge step up from the gas-powered, brightly painted, beaten down school busses everyone was then living on.

Camp in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, New Mexico, early 70s.

The Asp was sleek and beautiful, with long silver side panels and rounded airplane windows. Without a trademark psychedelic paint job on the outside, it passed unnoticed on the road. We were a hand-picked crew of a dozen, ready to drive night and day across the country in our vanilla-on-the-outside, richly collaged, tie-dyed hand-built-on-the-inside home. In 36 hours, we could sail the highways from LA to Miami, be there in time for a demonstration, a party, a festival—anywhere someone thought we could be useful.

I loved it like few other experiences of my life. For me, the Hog Farm was a Dionysian dream, a rich collection of experiences: people, events, cop shows, politics, celebrity, sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll. The bus was my home, a rolling party, a band of companions, a crystal ship cruising through the night. A young man’s dream.

In 36 hours, we could sail the highways from LA to Miami, be there in time for a demonstration, a party, a festival—anywhere someone thought we could be useful.

I left after a while because even all that was not enough. I slipped off the bus and lived in Oregon with the Prankster remnants for a while, then moved to LA to work in the movie business and to have different kinds of adventures. But the deep core of belief in people, the fundamental love that is the gift of Wavy Gravy, was not forgotten.

Baba Red Hat, Coconut Grove, FL, after the Winterʼs End Festival, March 1970.

Oh yeah, I guess I should mention here that for me, it was all about the party, but there were others who were a little more mindful. I don’t think I recognized that then. Wavy was Hugh Romney, a Merry Prankster legend, the Tom Wolfe Electric Kool-Aid guy directly connected to the Kerouac beatniks through Cassady, and Cassady was the real deal let’s party big time, got to get me some of that oh yeah, real deal. Wavy was also more than that, but I wasn’t interested in that part then. That comes later.

So I left the Hog Farm behind and I became successful, while Wavy and Jah and Larry and Girija Brilliant, Calico, Goose, Cedar and many others went on to India and some started SEVA, the charity that gave millions of people their eyesight back with fifty dollar operations. Others became part of a hundred other meaningful acts of caring, putting their lives where their ideals were.

Nowadays, when I reflect on paths taken and not, I am in awe of what they did. And regardless of my path, they kept me in their hearts and they stayed in mine. I would see them every five or ten years, and time went by.

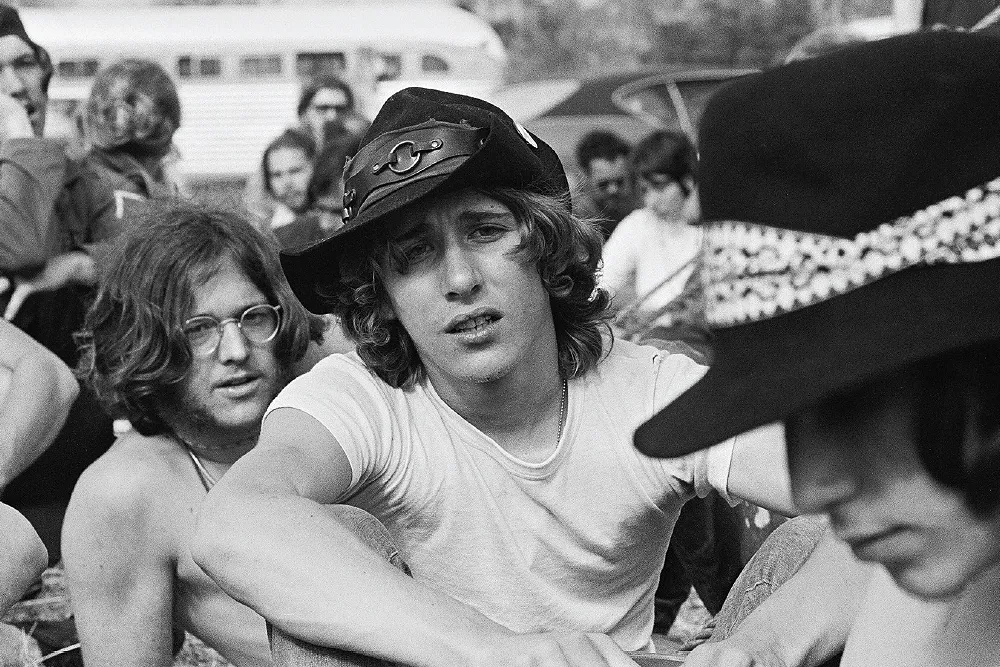

Winterʼs End Festival, Bithlo, FL, March 1970.

Too soon a 50th reunion was announced. It was to be a gathering of all of us, the ones from the beginning, the ones that came later, the children that came from all of this and their children, and the friends we made along the way.

These days, the Hog Farm owns a ranch outside of Laytonville, a town about two hours north of San Francisco; we gathered there. For a weekend, we peered into impossible old faces looking for our young beauty, and once we found it, it was as if the years had never happened. We talked and kissed and hugged and remembered, and for a while, we suspended time.

I brought a camera and made pictures to help me remember all I saw. On Saturday, I shot the whole family, everyone who could make it, and what a splendiferous assemblage it was. Then Saturday night, there was music on a stage, and a light show put on by some of the people who put light show into the lexicon of the sixties, and when I was tired, I walked away and went to my bed next to the stage and fell into asleep.

I woke around 2 AM to country silence and stepped out into the soft darkness of the night. Not far away in the center of the camp there was a campfire and people sitting around it, and there was quiet music.

Best seat in the house, the driverʼs seat of The Asp, our beloved bus, early 70s.

Wrapping myself in flannel, I walked over to the fire and stood there listening to Stacy and the others making human-scaled music, singing and playing for each other. I was transported to an understanding of music’s birth and how deep and old it is, and I was humbled.

When the fire softened, Kevin, the fireman, appeared. He circled the flames, a wizard at work, judging and placing a new log exactly, stirring and tending till the circle of fire was perfect again. I made some pictures, the scene so dark that each image came up a surprise. At some point I went back to my bed, grabbed a bottle of Irish whiskey, and brought it back to the fire for all. I stayed till 3:30, privileged and grateful to be part of this elemental ritual, and then I went back to sleep.

This is all we have, this and a thousand other moments like it: our bodies, our hearts, and our minds, our comrades and our family. These few precious moments while we are alive and know what a gift that is. What a great reunion. Even as I write this, I am alive again.